25th Graham Greene International Festival 2024

At the end of August I took voluntary redundancy from my Creative Writing lectureship at Nottingham Trent. Lack of teaching commitments meant that I was able to attend the annual Graham Greene festival from the very beginning (last year I dropped in for an afternoon, and heard Greene’s nephew Nick Dennys discuss Greene as a book collector and seller). As longtime readers will know, I have a deep interest in Greene, stretching back to my first term of doing a literature degree, back in 1977, when I read just about all of Greene’s novels during the space of ten weeks. My novel The Pretender features Greene on the cover. I invented a scene where, just before his death, Greene mischievously validates a forgery by my protagonist, Mark Trace at a key point in the story.

For five years I’ve been working on a novel about Greene’s three and a half months in Nottingham, which, I argue, were the most consequential weeks of Greene’s life. He moved into a boarding house a few minutes walk from where I live and had his only experience living in the North of England and his only encounters with the working class, in an area that still contrasts sharply with the smart, leafy town of Berkhamsted, where I’ve spent the last few days. In Nottingham, Greene trained (unpaid) to be a subeditor. Ten days after he left, he got the only proper job he ever had, on The Times. Even more importantly, it was here that Greene converted to Catholicism, taking instruction at St Barnabas, our Catholic cathedral. Largely because of this decision he was able to persuade his on-off girlfriend, Vivienne, to marry him. I’ve written about these events in a novel called Greeneland which I hope will be published around the centenary of the events it describes. (Queries to The North Agency).

In 2020 I was given a fellowship to explore the Greene collection at the Ransom Center in Austin in particular the two thousand (yes, really) pages of letters he sent to Vivienne during those fifteen weeks in Nottingham. Covid, then a bereavement meant I couldn’t go until this year. Kindly, the Ransom people kept the fellowship open for me. I was able to confirm the research I’d already done and made use of, as well as deepening my knowledge and adding a few grace notes.

The packed programme for the Greene festival can be found here. I missed the walk at the start of the festival. Satnavs, it turns out, aren’t much use on Berkhamsted Common, where Greene spent a lot of time as a boy and (maybe) played Russian Roulette in the trenches But I made a new friend. We had a good explore, then serendipitously hitched a ride back to my car, parked in the wrong car park.

The festival was chaired by Richard Greene (no relation), whose biography of Greene is definitive, and began with an interesting talk by Mexico expert Julia G. Young, who I had dinner next to the night before. This was on Greene in Mexico, where he set The Power and the Glory and travel journal, The Lawless Roads. Then Jon Wise, co-author (with Mike Hill) of the Greene bibliography that I put to good use at the Ransom Center, talked very knowledgeably about Greene’s autobiographies. Jon referred to some of the sections that Greene cut from A Sort of Life. There were two cuts to the Nottingham section, by the way, one after ASOL was first published. I’ll hold back on talking about them for now.

Nigel West (aka former Tory MP Rupert Allason) gave an in depth talk about Greene’s career as a spy and connections with Kim Philby. This was fascinating if dense material, so I won’t struggle to sum up. In a later talk, by Nicholas Shakespeare, we heard that Greene and Le Carre were rather insignificant intelligence players when compared to Ian Fleming, whose biography he has written. Shakespeare also knew Greene, who had encouraged him as a young writer, and had some great stories.

One of the more obscure parts of Greene’s biography is his relationship with the Swedish actor Anita Björk, which lasted for a few years in the second half of the fifties, not long after the suicide of Björk’s second husband, the acclaimed writer Stig Dagerman. Stig and Anita’s daughter, Lo, talked about her parents and her mother’s relationship with Greene. She was too young to remember her father but did have memories of Greene, a tall, benevolent figure. Lo’s was an unexpectedly fascinating talk and I was lucky enough to have dinner with her afterwards, so heard much more of her parents’ story and was given one of her father’s books. Lo, who lives in the US, hopes to translate her double biography of her parents, which includes three pages about Greene, into English at some point.

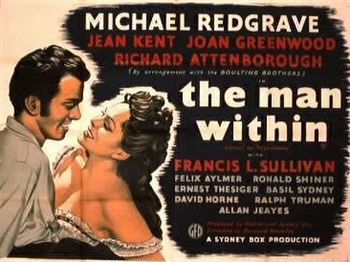

The first two evenings ended with a film showing. First came a little known (not even TPTV has it) 1947 adaptation of Greene’s first novel, The Man Within, which, to my surprise, was in technicolour. The film was rather better than I was expecting (the novel’s not great – Greene didn’t really get going until Stamboul Train in 1932) and includes Richard Attenborough as the rather useless protagonist with Michael Redgrave as the pirate mentor he betrays. There’s a strong homoerotic element that is, as I recall, absent from the novel. The ending is better than the novel’s, but the whole thing is still a mess.

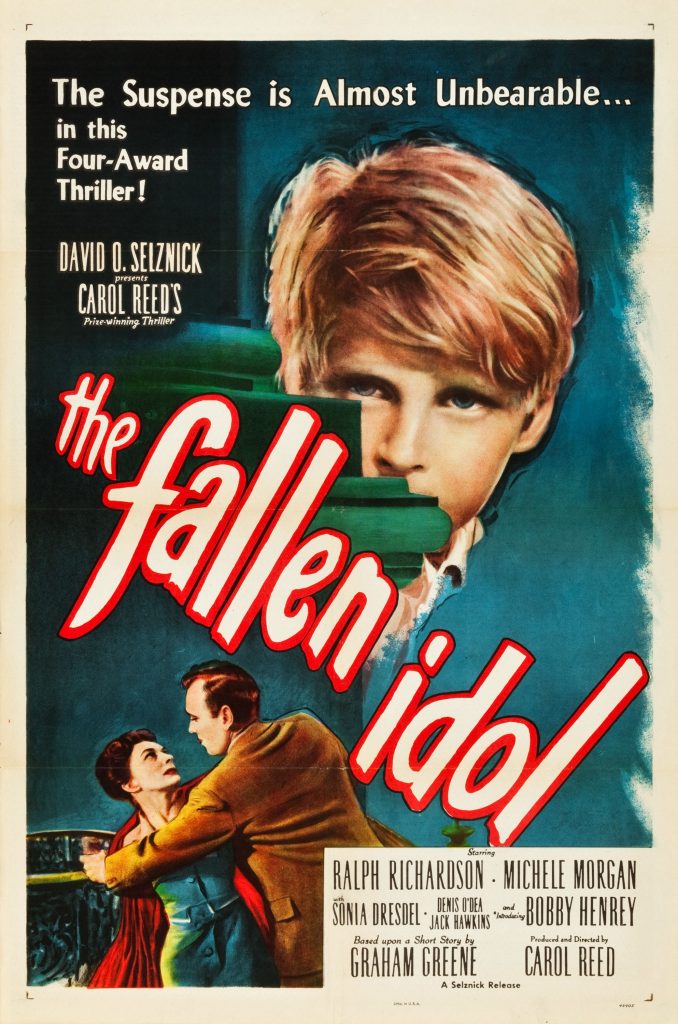

By stark contrast, Friday’s film, The Fallen Idol, is – after The Third Man – the best Greene movie, and it was terrific to see it on a big screen. I’d recently reread the story on which it was based, ‘The Basement Room’, so it was very interesting to hear Mike Hill talk about the process by which Greene and director Carol Reed expanded the story, and the difficulties they had with the child actor at its centre. (Mike also gave an entertaining introduction to the dodgier adaptation of The Man Within).

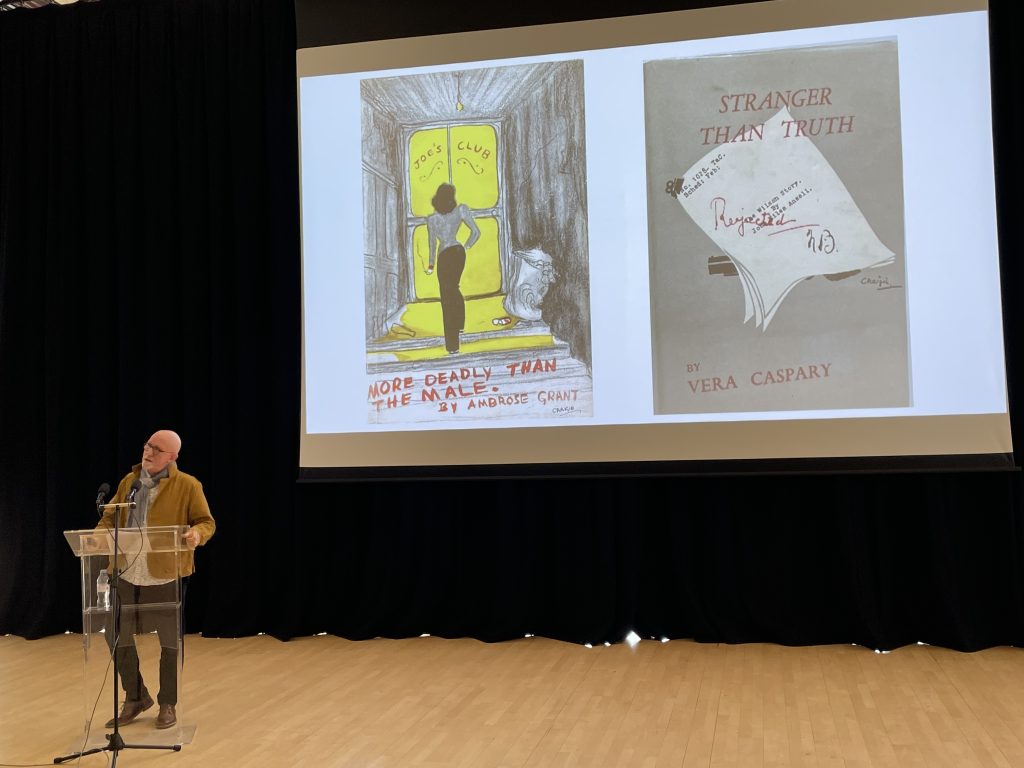

Historian Kevin Ruane gave a terrific talk on another neglected woman in Greene’s life. Like Anita Björk, Dorothy Glover never wrote about her relationship with Greene, and there is only one known photo of her, but their long affair was what effectively ended Greene’s marriage. She was his landlady’s daughter and he was living with her when his own home was destroyed in the blitz. As Greene’s wife observed, the affair saved his life. Kevin managed to dig out a great deal considering how little is known about her life, and even track down two letters from her (one to Greene). The couple collaborated on three picture books and Greene helped her get work as an illustrator. Examples of two covers by Dorothy were shown by Kevin below.

Randy Boyagoda gave a lively talk about being a Catholic novelist influenced by Greene (me too, though it sounds like his books are funnier than mine). Andrew Biswell talked about Greene, Brighton and the artist John Piper. The Saturday ended – for me, at least, I had a family engagement so couldn’t make the formal dinner or Sunday morning speakers) with a birthday toast from Greene’s grandson, Jonathan A. Bourget, who I’d had a good chat with earlier in the day, and who had brought with him a specially labelled and bottled pétillant white wine which was rather delicious. Thanks, Jonathan.

And thanks especially to Richard Greene, Mike Hill, Jon Wise and everybody involved in putting the festival together. I had a terrific time, spent far too much on books and met some brilliant people. I hope to be back again next year, when it will take place just before the centenary of Greene’s arrival in Nottingham. There’s a shedload of material and loads of recordings of invaluable talks from previous festivals at https://grahamgreenebt.org If you’re interested in Greene, I do recommend joining.