Small Hours: John Martyn’s Hard World

For the last three days, I’ve immersed myself in Graeme Thomson’s excellent new biography Small Hours: the long night of John Martyn, and Martyn’s music, which I’ve been listening to for 46 years. If you don’t know John’s work (though why else would you reading this?) here’s a playlist I made shortly after he died, aged sixty, in 2009.

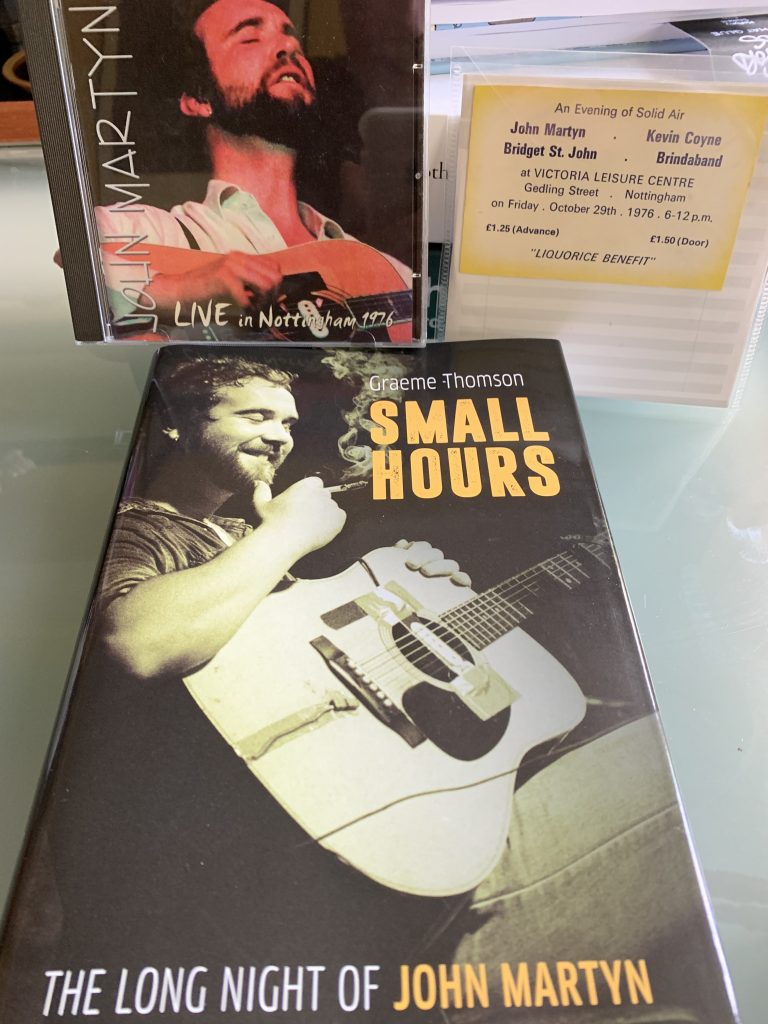

I discovered John Martyn in the mid-70s, when I was sixteen, and met him when I was 18, at a benefit gig for Liquorice. Writing for this fanzine had led to my studying in Nottingham, where I was in my first term at uni. I was on general hosting and recording duties. Martyn sound checked with a solid electric guitar, which he’d never used on stage before. One of us rushed to the cassette deck, but only caught the last two minutes of his improvisation. Later, I watched him snort something (heroin, I found out later) and found myself in an inadvertent staring match with him. When he met my gaze and stared at me intensely, I didn’t break my gaze, unsure how to behave in this odd version of an old children’s game. After an eternity, he abruptly turned away.

That night, following a fine show by Bridget and a mesmerising one by Kevin Coyne, John played a terrific set, one that included two songs which he didn’t release for decades. You can hear it on a semi-official CD called Nottingham 76, which seems to come from a third or fourth generation copy of the original (of which only two copies were made). I never made a cassette copy of my copy. By 2000, one of my two cassettes (the BASF Chrome one, which also had all of Bridget St John’s beautiful set) had disintegrated. The other, with 45 minutes on one side, and the encore of ‘Solid Air’ on the other, still sounded fantastic. I made a CDR of it which I sent to Martyn curator John Hillarby, who wrote the sleeve notes for the Nottingham CD, a copy of which he sent to me. The show has a lively, lubricated, late night crowd (the gig ended after midnight), with one bloke constantly calling out for ‘May You Never’, a request that Martyn continually bats back with wicked glee. ‘Later!’

If you go to the long established Big Muff website, you can find the interview Talking Through Solid Air I did with Martyn in January 1978. I’ve written about this on here before, so won’t tell the story again, except to add that the interview wasn’t prescheduled. John didn’t remember me or my article about Nick Drake, which he’d evidently praised. But, on arriving, he did ask the student organisers if anyone had any spliffs. I was hanging around and had brought a couple along. He asked what kind of dope was in them. I told him ‘double zero’. ‘That’s just Moroccan,’ he said, to which I demurred, but the joints got me the interview, during which we smoked them both.

I saw him four times over two years. He was at his most magnificent at the University of Leeds in March 77, previewing songs that would appear on ‘One World’, including the magnificent electric version of the title track which I berated him for not releasing. I thought for years that the electric band version had been lost (it’s not on any of the archival releases – I’m sure because, sad bastard that I am, I have them all). But while researching this piece I found this amazing performance, from the same week I saw them, with Danny Thompson playing up a storm.

I went to many more shows in the next three decades, including the 1980 Grace and Danger tour (on which his new band did only number from the album) and a 30th anniversary reunion tour, where a one-legged Martyn played ‘Solid Air’ in entirely the wrong order. But I went through a period of not seeing him, as his albums had lost their spark and his band gigs were less than thrilling. Catching him at Glastonbury 2000 made me realise that he had a great band again (he gets a cameo in my novel about that year’s Glastonbury, Festival), so soon after I went to see him at tiny Newark Palace Theatre, where he and his band of jazz musicians played up a storm, although Martyn’s singing and banter were almost totally incoherent. At the interval we asked the woman behind the bar what else was in each of the half pints of coke he kept knocking back.

‘Eight bacardis,’ she replied.

There have been a couple of John Martyn biographies before, but both got poor reviews and I couldn’t bring myself to read his ex-wife Beverley’s memoir, which laid out his violence and neglect of his children. Small Hours, thankfully, is the biography that the artist deserves. My only quibbles with are minor (no index, occasionally hard to follow chronology, but mainly, I wish it were longer). While Thomson recognises that Martyn was highly intelligent and could be charming, he clearly demonstrates that he was also unhinged, an increasingly chronic alcoholic, prone to violence, deeply self-destructive and, especially when it came to the women in his life, could be a total shit. Little of what we learn is surprising, though I was taken aback to find that, touring in the early 70s, when his marriage to Beverley was at its best, he began an affair with seventeen year old support act, Claire Hamill, one that continued on and off for years.

Thomson writes well and has interviewed the people you’d hope he would. Another of my musical heroes, Richard Thompson, blessed with the memory of someone who didn’t drink or take drugs, contributes often, little of what he says being kind, although most of it sounds fair. Thomson gives a balanced assessment of Martyn’s life and work. My main complaint, frankly, is that it should have been longer, with even more space given to the 70s work. The genesis of the song ‘One World’ for instance, is interesting. The hard electric version I loved (the OGWT one) was preceded by a song with a different lyric but similar tune, called ‘Anna’, and has a self-mythologizing lyric that tells you a lot about how Martyn saw himself: ‘Grew up in a dirty town where they like to kick you when you’re down/If you show an easy side they take a knife and cut you wide.’ But Thomson’s account of the One World sessions and his assessments of the work are insightful and astute (I liked, for instance, how he uses Martyn’s cover of the traditional ‘Spencer the Rover’ as a way to discuss how Martyn could never write story songs, in the way that say, Richard Thompson does, and that many Martyn songs have an unfinished, semi-improvised feel: which is, of course, part of their charm.)

I only felt Martyn’s anger for a flash, when I brought up Nick Drake, who was a sore subject with him. He hated how his friend, so starved of critical attention in his lifetime, was being acclaimed only after his death. Thomson has a theory that John wanted to be Nick Drake. He also casts doubt on Martyn’s last meeting with him. Martyn didn’t tell me about that, but he did discuss it once in a 90s radio interview. Moreover, what he says about the last meeting is backed up by Drake’s father’s account in Remembered For A While.

One shocking revelation in the book is that, on getting a call about Drake’s death, John laughed, then called to Beverley, ‘He’s done it.’ People have odd reactions to death. It’s understandable, though, if, spending years on a biography, you come to dislike its subject, and there’s no doubt that Martyn could be a bullshitter. The way he treated his children and stepson was monstrous. Towards the end, he seems to have reconciled with Vari, about whom he wrote ‘My Baby Girl.’ His son Spencer worked with him and soon found himself sucked into substance abuse.

There are endless tales of appalling behaviour, selfish, unhinged stuff from a man who attracted hangers on, loved to hang out with criminal types and devastated several lives. And yet, and yet. What songs he wrote in his prime, what a beautiful man he was, and what a wonderful musician. You’ve got to separate the art from the artist, or you’re left with very few artists to admire. And, of course, Martyn had a very sweet side, which didn’t only come out in his songs. Nice to read that John had a warm reunion with Bridget St John not long before he died.

I mentioned that one of two Liquorice tapes (including all of Bridget’s set) was destroyed, but the second wasn’t, so here’s the final section, from when I transferred it to CD about 18 years ago. The copyright on this stuff is dubious, but I pressed ‘record’ that night, which, morally at least, gives me some right to post it here. Sadly, the two minutes of soundcheck is long gone and the 17 minute ‘Outside In’ is too long for my file size limit. Below you get – in order – ‘Over the Hill’, a beautiful medley of ‘Make No Mistake’ and ‘Bless the Weather’, ‘May You Never’, a fiery ‘I’d Rather Be The Devil’ and a beautiful encore of ‘Solid Air’. But first, from the semi-official, lower quality release, a song he debuted that night. As I recall, he’d brought along an old acoustic guitar to play what he called ‘My Val Doonican number’. I heard him play this again five months later in Leeds, but he didn’t record it for another thirty years, in a much inferior version with changed lyrics. It’s a beautiful lullaby called ‘One for the Road’ and it’s Martyn at his most loveable, the pastoral idealist who broke through with ‘Bless the Weather’ and, for the next few years, made innovative, mesmerising music, full of love and rage. You wouldn’t want his devils in your life. But oh, those angels…

Thank you so much for your recordings best gig ever as the 2000 show at Avalon Stage Glastonbury the arrangements just higher musically breathtaking intelligent I would love a recording of that one so much . Maybe the BBC broadcast it?

There were no cameras or recording equipment in the tent that night but agree, it was a terrific set. My thoughts on it are in this blog, written at the time. http://www.davidbelbin.com/2010/06/glastonbury-2000-part-4-saturday/ As I recall, there’s also a mention in my Glastonbury novel, Festival, but it came out nineteen years ago, so I’m not certain.

Big John was, and is, still of the Greatest !

Luv

Raphaël

France