The Great Deception

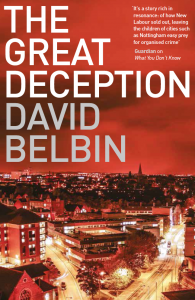

Just listened to a wonderful Desert Island Discs with Lemn Sissay, who, at one point, talks about people deciding to ‘knit me a novel’. It got me thinking. Today, I want to tell you about the new Bone & Cane novel, published this year. I don’t want to dwell on why it’s a year or two late, largely due to the collapse of my old publisher and the need to find the right new one. Glasgow’s Freight Books have done an excellent job with it. Look at the great cover above.

Instead, let me tell you about the different threads I knitted together to create this story, my most ambitious to date. It has three main time periods (and three smaller ones): the late ‘60s, the early ‘80s and the late ‘90s. The stories in each bounce off the other, demonstrating the way that secrets kept can resonate through the years. Or, to quote Faulkner, in Requiem For A Nun: ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’

When you start writing a sequence of novels, you don’t know that there’s going to be another one. This was the case with Avenging Angel, the story that led to The Beat series. It was also the case with Getting Your Betrayal In First, the novel that then became Previous Convictions and, finally, Bone and Cane. So, when I made my protagonist, Sarah Bone’s, grandfather a cabinet minister in the Wilson years, I didn’t know I was going to write about him. Ditto her father, whose ‘80s death from AIDS motivates Sarah’s campaign to halt the spread of HIV in prisons.

But, by the third book in the sequence, I wanted to explore both characters. I’d also long wanted to write about PM Harold Wilson, and worried that David Peace would beat me to it. Wilson was the defining political figure of my childhood and early immersion in politics. I was doing Politics A level when he resigned suddenly in 1976. I’ve long been fascinated by the reasons behind that, which are part of this book. Then there’s the Spycatcher scandal, which is tied up with the attempted establishment coup against Wilson (which partly inspired Chris Mullin’s A Very British Coup, where the PM is more of a Corbyn figure). Peter Wright, and that putative coup, are part of my story.

Sir Hugh Bone’s relationship with his son, Sarah’s father, are also at the heart of the novel, much of which takes place when Sarah is a child, and before her dad has left the UK for Majorca, where he died. The second storyline is, if you like, the origin story for the whole sequence (and it’s fine, by the way, to read the novels in any order, although What You Don’t Know is out of print for now and currently costs a fortune, but is available on Kindle). It shows what Sarah and Nick were like as a new couple, visiting her grandad in Derbyshire and her father with his lover in Majorca.

The present day part of the story is to do with Sarah’s complicated relationship with her mother, who is dangerously ill, forcing Sarah to take a sabbatical from parliament. Nick, meanwhile, is trying to ‘rescue’ Nancy, a former girlfriend, who is now a crack addicted prostitute. His old friend Andrew Saint gets involved. But he has problems of his own. The three stories are carefully interweaved (a humongously complicated job) to keep the reader in suspense and, to paraphrase the master, present the problem in the best possible way.

I think that’s enough about the story, which you can order now (eBook available shortly). If you’re in Nottingham, and would like to hear more, do join me at the launch on October 21st (7pm, free, no need to book) upstairs at Rough Trade, on Broad St, Hockley.

But back to the epigram. In fifty or so novels to date, I’ve not used an epigram, but this novel seemed to require one. At one point, it had three, the Faulkner one cited above and a second that, in the end, I also decided was too well known and on the nose: Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Three can keep a secret, if two of them are dead.’ For that’s the point about secrets, that once you share them with anybody, they’re no longer a secret.

But my first choice of epigram is the one that remains. My old friend Mahendra Solanki wrote it out for me after I heard him read it as a new poem a few years ago. It went on to become the title poem of his fine Shoestring collection The Lies We Tell, published last year. It goes like this:

After a while, you believe the lies you tell

I think the line does what an epigram ought to do: intrigue the reader and introduce a theme, adding an extra angle to my story without illustrating it. I took Mahendra a copy of the novel yesterday and I hope, after he’s read it, he’ll be pleased by the use I’ve made of his words.

Finally, the title. For a long time, I had no idea what to call this one. Then, one Christmas, we were driving back from London, listening to Van Morrison’s Hard Nose The Highway. Not his very best LP, perhaps, but it contained the first Van song I ever heard, aged 15, when Bob Harris played it, under some quirky silent film footage, on ‘The Old Grey Whistle Test”. I turned to Sue and said, ‘what about that for a book title?’ Once we got home, I googled the title, fearing that some other bugger would have already used it for a novel, as they usually have. But they hadn’t. And it’s a great, great song. Van at his bitterest and most oblique. Have a listen and, if I’ve succeeded in interesting you, please buy a book!

(PS and, if you like it, I’d really appreciate any reviews you have time to write on Amazon or elsewhere – they really make a difference)