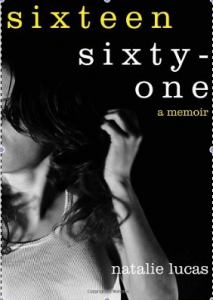

Love Lessons Redux: on Sixteen, Sixty-One – a memoir by Natalie Lucas

I’m not much given to reading memoirs, unless they’re by writers I already like a great deal, but this book’s subject matter appealed to me (and it’s still only 99p on Kindle) as it covers territory that I’ve written about in two of my novels, Denial and Love Lessons (eBook edition coming soon). In each, an underage girl sleeps with an older man: 23 in one case, nearer forty in the other, and the man’s exploitative behaviour is demonstrated, then skewered. There’s a moral element, of course, in that YA fiction is for emerging adults and the novel acts as a warning to young people tempted to have sex with an unscrupulous teacher (or, for that matter, university lecturer). Not long after I wrote Love Lessons, the law was changed so that it became illegal for adults with authority over young people to have sex with them before the age of 18 (before that, it was sixteen). Going into schools to talk about my book and reading about the events at Chetham’s School of Music over the last twenty years, it’s clear how necessary this change in the law was.

But it wouldn’t have helped Natalie (a pseudonym), for her abuser wasn’t a teacher, but a family friend. And I use the word ‘abuser’ deliberately: he was 61 when it began, she 16. I read this book very slowly, with frequent breaks. Partly because it was on the Kindle, and I prefer paper books, but mainly because it’s an extremely creepy, uncomfortable read. Look, this is my territory, but I couldn’t make this stuff up. Young people can read against the grain of the writer’s intent, thinking the affair in Love Lessons is a good thing (I added an author’s note, just in case they missed the point). Here, I defy any reader to admire the abusive adult, who seduces Natalie intellectually by making her feel special, part of an elite (as self conscious adolescents often yearn to be). The way in which he steadily becomes more and more of a monster is deftly handled. Most readers will work out how awful things have become long before Natalie does. There’s a What Maisie Knew-like horror about the narrative. There are times when the narrator still does not seem to have sufficient distance from her subject matter, which is hardly surprising and a long American section which acts as a relief but is also rather skippable. Overall this is a brave, frightening memoir that grips as you shudder.

And this all happened recently (there are scenes set at the last Glastonbury Festival I went to), more recently than Stuart Hall and Jimmy Saville’s offences, long after the 60’s, when the new permissive society deemed it acceptable for rock stars to boast about sleeping with 14 and 15 year old girls. There’s still nothing illegal about the guy’s behaviour and he gets to keep his anonymity. But not, one hopes, his self respect.