The Old Guys: Martin Carthy, John Cale & Van Morrison

I go to gigs most weeks. Every year there tends to be a week where I have several. This week, it was five (nearly six, as I originally planned to see Nadia Reid at The Bodega on Monday). That’ll seem like overkill to some, but last year I was at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, where I would sometimes see five acts in a day, and I’m a regular at Green Man festival, where I’m likely to see even more.

The week was bookended by shows from two bands whose front-men are 58, a few years younger than me: Mercury Rev’s Jonathan Donohue at the Rescue Rooms and saxophonist/band leader Tony Kofi at Peggy’s Skylight. I’ve seen both many times before. Each band was in great form. Tony’s had the great Pete Cater on drums and featured a second year conservatoire student called Olly Young on guitar. He had learnt the guitar parts for a Lou Donaldson tribute in less than 24 hours, when the regular guitarist had a bereavement, and did a fine job. Today, however I want to write about the middle three, who had a combined age of 245: Van Morrison, John Cale and Martin Carthy.

I last saw Van at Nottingham’s Royal Concert Hall some thirty years ago. I’d been going to his shows since 1979, when I saw the same tour twice in a fortnight. The first time he was transcendent, the second, despite exactly the same setlist (bar my favourite song, St Dominic’s Preview, which didn’t help) and a better seat, he phoned it in. And so it continued. I saw two fantastic shows in Sheffield (my home town) and Nottingham with Georgie Fame, who seemed to bring out the best in him. But on the Enlightenment tour, he was lack-lustre, until he came back on for a half hour encore of new material, which was sublime. Then there was the nadir, a show where he handed what seemed like half the vocals to his support/sidekick Brian Kennedy. I was in the middle of the second row and at one point I heard myself heckling. Van looked confused, he never got heckled. But he deserved it. I vowed never to go again.

My will eventually broke. After all, that run of albums, from Astral Weeks through Veedon Fleece, is possibly the strongest consistent run from all the great 70s artists (Neil Young and Joni Mitchell just about equal it) and I thought I’d like to see him one more time before he (and I) got too old. Van turns 80 this year. Actually, I bought tickets to see him last time he played Nottingham in 2019, only for Teenage Fanclub to announce a Rock City show. I sold my ticket on and I’m glad I did, because it was the last time TFC’s original line up played here, but that night Van played St Dominic’s Preview, which I’ve only heard him do the once. That said, reports did reach me that, overall, it wasn’t a great show.

This time I didn’t try to persuade anyone to come with me. It was the opening night of a short tour and my expectations were low. I forked out ninety quid for a good seat and found my place just before Van came on, five minutes early. His backing band had just played a short opening set and what a band they were, a stonking six piece plus two singers. Van had shrunk and looked, beneath his hat and shades, fairly trim. I didn’t know the opening number, Only a Dream, but he followed it with the title track of his last good album, Back on Top, and it became clear that not only was he singing well, he was enjoying himself, feeling out the new band, happy with how it was going. Here’s the setlist.

Van, it turns out, has got past the period where his albums were going through the motions cover versions (or worse, lockdown rants) and written a set of new songs reminiscent of his best work, One of these, Down to Joy, he sang well. He didn’t just sing. He played sax, a lot, and guitar, and harmonica. He even, for a powerful Vanhose Stairway, performed at the piano, only his hat visible to the audience. He pulled out songs I hadn’t heard him do in 46 years, like Wild Night and Help me. And he encored, of course, with the first record of his I bought, Them’s Gloria, leaving the band to vamp on for ten minutes after he’d left the stage, having performed his regulation 90 minutes. Was he as good as I’ve ever seen him? No, but he was the best I’ve seen him in 35 years. I’m very glad I went.

Here’s a bit of Wild Night – right hand side of the stage only: the lady in front of me had big hair.

If Van was in good form, John Cale, who has just turned 83, was in tremendous shape. I’ve never paid close attention to Cale but my friend Michael is a huge Velvets fan, who once had coffee with Cale. The Lou Reed ‘Berlin’ show we had front row seats for back in the noughties counts as one of the best gigs either of us have ever been to. The only post-Velvets Cale albums I’ve listened to much are June 1st, 1974 and Songs for Drella, though I do have Paris, 1919 (the one with ‘Graham Greene’ on it) and had listened to the new one for research purposes. Also sitting with us was my old university friend Ian (from whom I took over the editorship of the student union fortnightly Gongster’s music pages in 1978), who has seen Cale some fifteen times. He assured me that this gig, at Nottingham Playhouse, was in the top half of those, probably the top five, and I can believe it. Cale played guitar early on, did his splendid version of Heartbreak Hotel as well as a tribute song to and a cover of a song by Nico (who he produced as well as played with), and, after many had shuffled out, returned for a terrific, superbly arranged encore of the Velvet’s I’m Waiting for the Man. Did I love it? Yes and no. I can see what all the fuss is about Cale without especially feeling the music. There are plenty of other acts I feel the same about (Radiohead, Elbow, Nick Cave, to name a few). But the Caleheads got a career spanning set, with rare nuggets, and Cale was in strong voice, with a crack band. Indeed he seemed, at 83, to be at the height of his powers.

Which leaves me with the difficult bit. I’m not a hardcore folkie. Back in the late 70s I hung out with people who were. I even went to a couple of Cambridge folk festivals (77 & 79). I also performed my early poetry and some parody songs in a couple of folk clubs. My favourite Nottingham gig was by Nic Jones at the Boulevard Folk Club in Radford. I’m still a fan of his work from that period. Through my neighbour Al Atkinson (a fine folk singer until repeated bouts of Covid did for his voice) I’ve attended Nottingham’s oldest folk club, The Triangle, in The Gladstone pub just up our road, a few times. Through Al, I got to know the work of his friend, the legendary Annie Briggs, the two of them having started out as singers following the impetus of the Centre 42 Trades Union cultural bonanza of 1962. Another old friend of his is Martin Carthy, who he’s known since the 70s. I first saw Martin many years ago, playing with the late, great Dave Swarbrick. He and Martin made several albums together before Swarb joined Fairport (I am, predictably, a big fan of Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny).

So when my mate Rob told me that Martin was playing, virtually unpublicised, a small hall (the Squire Performing Arts Centre) attached to a nearby posh girls’s school, we bought tickets. Mutual friend Michael came too, so we got to compare 83 year olds on consecutive nights. I had been warned that Martin was very frail these days. My friend, Prakash, on the bus back from Van Morrison, told me that, when he played Peggy’s Skylight recently, Martin was having trouble playing and singing at the same time, and kept forgetting things.

We arranged to meet Martin before the show. Al asked him if he still played with his daughter, Eliza. No, he told us, because I keep forgetting things. ‘It’s OK to embarrass yourself, but not your daughter?’ I asked. ‘Oh I don’t mind that,’ he said. We talked a bit about how, like Bob Dylan (who, in 1963, he taught Scarborough Fair to, Dylan basing Girl From the North Country on his version) he kept going. He hadn’t seen Dylan for years and I tried to convince him that Dylan had improved his singing considerably since recording his Sinatra cover albums and making the tremendous Rough and Rowdy Ways album.

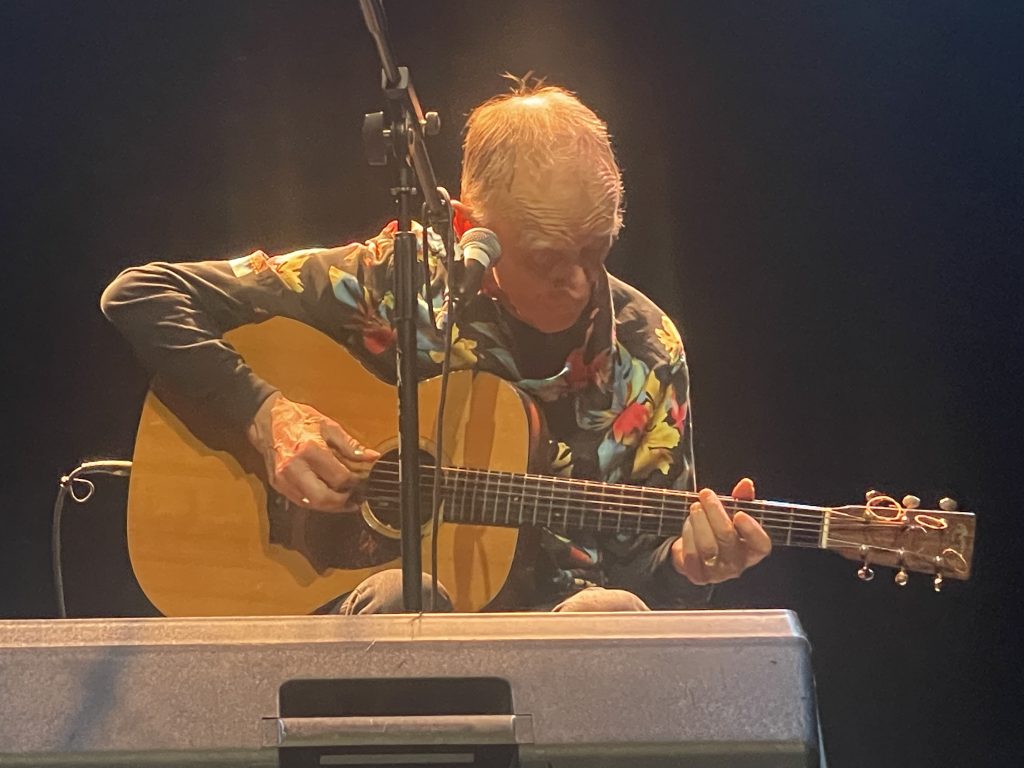

Below, Martin and Al before the show.

The show was divided into two sets. The first one was low key, with some nice stories and a few forgotten verses. The highlight was the last song, with Martin explaining how he had been brought back to singing the next song after the BBC invited him to Scarborough to record a version with the original set of lyrics. A sublime Scarborough Fair followed, then a twenty minute break. During the break, a few people, including a couple of friends we’d caught the bus with, decided to leave, embarrassed to see this old man on stage, playing well, but singing in a frail voice, repeating himself a little, forgetting things a lot.

Should I be writing about this? It’s something I’ve struggled with. Al and I took the bus home, agreeing we both felt we wanted to write about the evening (I showed this piece to him before posting it). Neither of us were sure how to.

Things got worse in the second half. However, before that, they got better, with Martin having warmed up. He talked about the sole influence on his becoming a folk singer, the great fisherman singer Sam Larner, who he first saw when he was seventeen. He played us one of Sam’s songs, promising to play another later. He talked about Ewan McColl and the awe with which he viewed Larner, who he wouldn’t dare to sing alongside. Best of all, Martin sang a sublime version of the old folk song ‘Young But Daily Growing’, which is widely regarded (Al told me) as the song which most tests whether a singer has what it takes to be great. I knew it first from the Basement Tapes version by Bob Dylan and the Band. It’s known in folk circles as ‘The Trees They Go So High’. ‘That was worth the price of admission on its own’ Al told me when he’d finished it.

Martin scrolled his phone, looking for songs that he knew he could perform by heart. Sadly, he kept failing. A Begging I Will Go, he attempted three times. Maybe he’d have been better off performing instrumentals. Maybe he could have done what Dylan does, using a crib sheet (if you sit close enough you can see them on his keyboard), perhaps on a music stand. But that’s not the folk way (in fact, Al says, this aberration is generally taken a dim view of by the old guard of the folk scene).

Martin asked for suggestions. I reminded him he’d said he’d do another song by Sam Larner. He replied that he wasn’t quite up for that but sang a bit of one and told some more stories about Sam. By now, 90 minutes played, the gig should have been over. Martin was looking for the right song to end on. Everything he tried, he forgot, at one point getting prompts from another folk singer in the front row. Then she didn’t know the next verse of The Ballad of Springhill, so he tried another. It was more like someone’s front room than a folk club, never mind a theatre. Yet, you know what? It felt fine. A little sad, sure, and I can understand why it made some people feel uncomfortable, but I’ve got a 92 year old dad whose short term memory is completely shot, yet who is generally happy. Martin’s a long way from that, While he kept muttering ‘the shame’ when he forgot something, he clearly wasn’t ashamed, he wanted to keep playing. The second set overran by half an hour. Eventually he gave up trying to find a song he could recall all of and performed a short acapella piece with prompts from his phone (oh, irony). The evening was, in its way, profoundly moving. The applause was long and warm.

‘I’ll be better next time,’ he promised us when we went to say goodbye afterwards. He probably won’t be and it doesn’t matter. We were privileged, once more, to see a great figure with a direct connection to hundreds of years of folk tradition. Living history, you might say. And while it was in some ways the least of the three shows I saw over four nights, it’s also the one I know will stick in my memory longest.

After all, Van Morrison used to shout as much as sing: It’s too late to stop now.