May reading: in and out of lockdown

This blog can also be read on the Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature website.

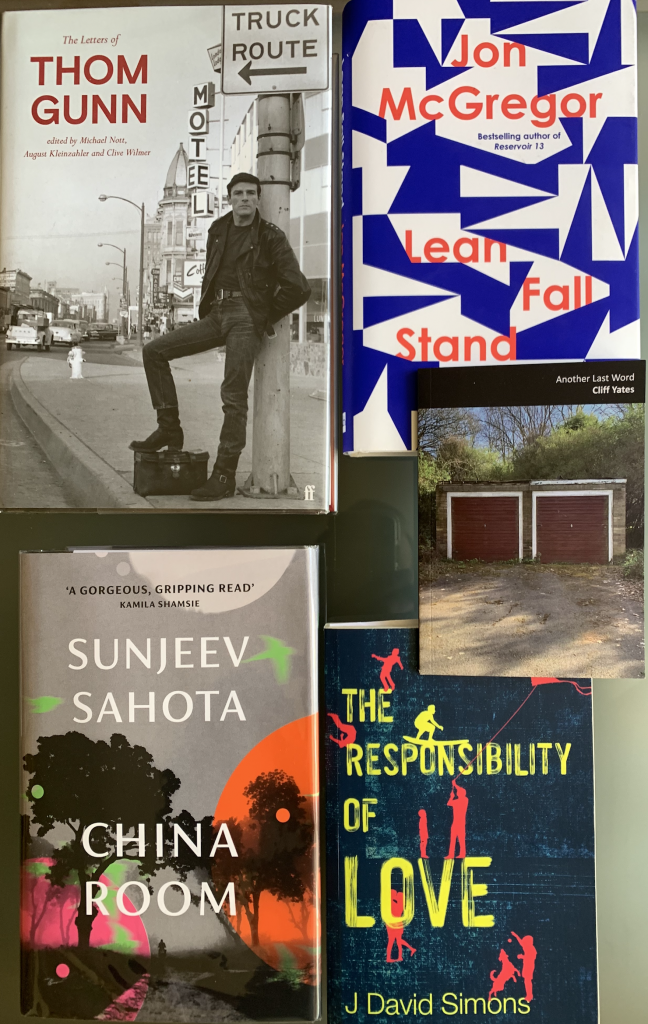

I’m a sucker for a good Antarctic or Arctic story. My favourite in this genre is Trevor Griffiths’ seven-part TV telling of the Scott expedition, The Last Place on Earth, from the mid-eighties. I was reminded of this recently by the harrowing TV series, The Terror, which is a fictionalised version of the ill-fated Frankland expedition in search of the North-West passage through the Arctic. Then there are Thomas Kenneally’s two fine novels The Survivor and A Victim of the Aurora, both from long before he won The Booker Prize with Schindler’s List. Each made a big impression on me forty years ago. To these can now be added Jon McGregor’s Lean Fall Stand which details an Antarctic survey gone wrong through three viewpoints: exhibition rookies Thomas and Luke, along with technical coordinator, Doc (aka Robert). They take a small risk, with deadly consequences. The Antarctic section is vivid, the detailed research is worn lightly and our sympathies are split between the protagonists.

My copy of this book was bought from Five Leaves Bookshop and personally delivered by my neighbour, its author, but I’ll try not to let bias what follows. Reading conditions matter, however, so I should say that my partner read this whole novel when we were away on a short break and loved it. My enjoyment may have been marred by reading the second half after we got back, in between marking student dissertations. For me, the halfway point was where the book began to drag. There was nothing much the reader was waiting to find out. The final section about stroke rehabilitation is interesting, but had me crying out for the experimental techniques of B.S. Johnson (House Mother Normal) to convey one character’s struggle to recover from their Antarctic catastrophe. There’s a very good coda, but – with my novelist’s hat on – I thought it was written from the wrong point of view. I wanted to hear about a point of view character who disappears in part one, but the final point of view turns out to be that of Doc, who is not a particularly interesting (or sympathetic) protagonist. His wife Anna’s point of view is the predominant wone in the novel. She’s stayed with him because she likes having a husband who’s mostly elsewhere. Until he isn’t.

In a recent interview for Five Leaves Bookshop, Jon talked about how writing the short stories in The Reservoir Tapes for Radio Four helped him learn to write more concisely and develop a facility for suspense. This shows in the superb opening section (and in those stories) but not when it comes to dealing with an inquest or one character’s decision to lie to protect another. It was suggested (by a friend who heard the radio serialisation) that the suspense issue could have been resolved by restructuring the novel so that it works through flashbacks, creating a mystery about what happened on the ice, but McGregor isn’t setting out to write a mystery, and that approach would have cheapened the writing. You won’t regret reading this novel, but, for me, McGregor’s masterpiece remains Even the Dogs. My partner, by contrast, reckons it’s the author’s best novel to date. In particular, she found the account of how the stroke victim’s wife has her career derailed convincing and compelling. It’s a thing I like about McGregor’s fiction, how his stories often divide readers. Not only that, but everyone disagrees about different novels. Long may he defy consensus.

McGregor’s novel was inspired by an abortive trip to the Antarctic seventeen years ago. Sunjeev Sahota’s third novel China Room was instigated by his return to the family home, helping to run a corner shop near Derby while his father recovered from illness. I was involved with the now sadly defunct East Midlands Book Award, for which Sahota’s first novel Ours Are The Streets was shortlisted, and was even more impressed by its Booker shortlisted successor The Year of the Runaways. This novel is on a different level again: quieter, tighter, superbly written and structured, telling the tale of two protagonists, four generations apart. We read about an arranged marriage in rural Punjab a century ago. Fifteen-year-old Mehar is wedded to one of three brothers, but isn’t allowed to know which one it is, and neither is the reader. The confusion is skilfully done. You never doubt that you’re in the hands of a writer in full command of his material. Just when you’re starting to figure out what must be happening, the story skips to the present day, and a protagonist who finds himself in the same building that his (slight spoiler alert) great-grandmother lived in. Why has he been sent there? I’m giving nothing more away, except to say that this is a very tight novel which gives as powerful an impression of the Punjab as McGregor does of Antarctica. This is a superbly structured work, full of suspense, much shorter and tighter than its predecessor, and deserving of every prize going. Third novels are often the crucial ones (just as third albums are for bands) and this will, I hope, raise Sahota to a new level.

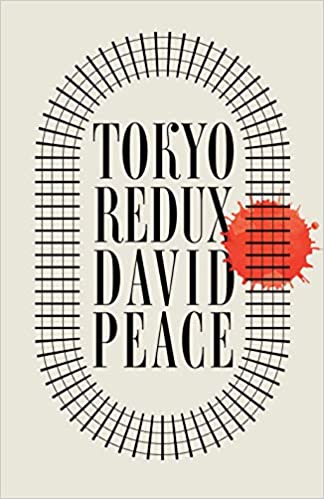

I’ve had a proof copy of David Peace’s eleventh novel Tokyo Redux since last March but avoided reading it because I wanted it to be fresh in my mind when I interviewed him for Five Leaves Bookshop. Tickets were about to go on sale when the pandemic hit and the event is no longer on, so I decided to read it before the reviews were out. It’s the final novel in Peace’s Tokyo trilogy, over a decade since its predecessor, Occupied City. That one used a Rashomon-type structure to tell the story of an outlandish robbery, pretty effectively too – each new point of view changes our perspective, adding to our understanding of the whole. Only after reading all of the points of view can one get a sense of what really happened. After that, Peace, arguably, got sidetracked by his research, first writing a rather good novel about Rashomon’s author, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Patient X. Peace next wrote a novel about Bill Shankly, Red or Dead, which even this Liverpool supporter found rather heavy going. His Red Riding quartet remains, justifiably, his most highly rated work. He’s an inventive, hard-nosed writer with a vivid sense of pace, one who has outgrown the occasionally invidious early influence of James Ellroy (whose work I have mixed feelings about) and tells nuanced, rich, complicated stories.

Tokyo Redux goes deeper and deeper into the theories around the death (murder? Suicide?) of the Head of Japan’s National Railways in 1949. It’s absorbing and, at times, exhausting, weaving together post-war Japanese history, the Allied occupation of Japan, the disappearance of a pulp fiction writer and a complicated murder mystery. It’s not an easy read, but it always kept me interested. You need your wits about you. I finished it exhausted but in a good way. Peace used to say that he’d only write twelve novels, then devote himself to ‘bad poetry’, but we have enough of that already, so I hope he recants. If not, fingers crossed his next and twelfth novel, is UKDK, a novel about UK politics in the 70s, which he’s been promising for years.

Our house (and allotment library garage) are now full to bursting with books, so I’ve taken to borrowing more books from the library. Credit to Bromley House for providing the Thom Gunn and Sunjeev Sahota as soon as they came out. If you can afford to, do consider joining them. It’s a wonderful place and deserves lots of new support after the year we’ve all had. The other really useful thing about library books – especially new ones – is that you only get three weeks to read them, which, with reading piles the size we have, is a useful discipline.

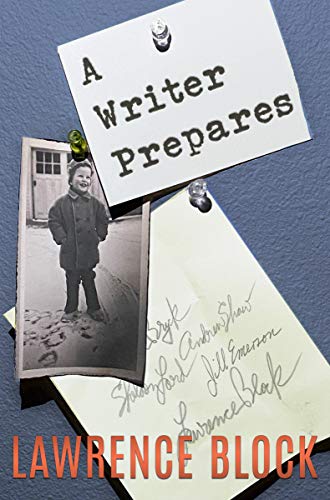

More briefly, Lawrence Block’s A Writer Prepares is a real treat. As a long-time fan of the author, I thought I knew his stories about the early days of his career as a pulp fiction author. He wrote paid book reports for an agency along with quick turnaround commissioned fake true-life accounts, torrid erotica and lesbian paperbacks under a variety of pseudonyms. Hell, no, there’s loads more to hear. This book, begun decades ago, rediscovered and finished by its 82-year-old author, is terrifically entertaining, and I rationed myself to short sections in bed. Late on, the author, his final section interrupted by the pandemic, reflects on how memories change and friends long gone. Here he finds a modest profundity that Block is always eager to deflect yet, but is at one with the worldview at the heart of his best work. A master of memoir as well as crime fiction, then.

I’ve also been rationing the Collected Letters of the poet Thom Gunn, limiting myself to a year at a time and occasionally photographing letters to reread later. This excellent collection, edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler and Clive Wilmer include numerous references to contemporary culture and fascinating accounts of taking acid and other drugs, but the key material is about the poetry. I particularly liked two lengthy letters to Gregory Woods, my erstwhile colleague, and the UK’s first professor of Gay and Lesbian studies. The first is from when Greg had just finished his PhD. It included a chapter on Gunn, which he sent to the poet. Gunn’s reply, telling Greg that he’d got virtually everything wrong, is funny, generous and, of course, self-serving. You get a strong sense of the man (one of my favourite poets, but an uneven one) from these letters, which I recommend highly.

It was odd, realising that, on our one visit to San Francisco, we ate breakfast most days at a café just along the street from Gunn’s home on Cole. Gunn is modest about his talent and clear on the cost of teaching in a university, a job he nevertheless clearly loves and which kept him from some of the excesses he was prone to. Methamphetamine hastened his demise from a heart attack, aged 74, but, for all his friends’ distaste for his sex and drug benders, the (few) late letters make clear that Gunn made a clear choice about what he was getting into, knowing it would hasten his death. Throughout, he’s an entertaining correspondent. One grows to like Gunn more as the years go by (not always the way). The 80s are a tough read. Gunn avoided the HIV virus and it’s affecting to read his letters to friends abroad about his many friends dying of Aids, and see the stoical help that Gunn gave to many of them. This period led to the collection that, for many, is Gunn’s best, 1992’sThe Man With Night Sweats. Must reread that soon.

The only complete poetry collection I read in May was the short, snappy Cliff Yates’ Red Ceiling Press chapbook Another Last Word, which consists of the poet bickering with his wife during lockdown. Many of us will recognise our relationships in these poems. I’ve been enjoying Cliff’s poems since his debut, Fourteen Ways of Listening to the Archers in 1994 (and I don’t even listen to The Archers, except under sufferance). A gnomic, surreal streak runs through them. The poems here, however, tend to be more down to earth.

MAKING THE GRANOLA

‘The fact that I think it needs doing

means that it needs doing,’ she said

‘and the fact that you think it needs doing

Is neither here nor there.’

It’s a very funny, rather brilliant book. I loved it.

J David Simons has been one of my favourite authors since Five Leaves took over publication of his Glasgow to Galilee trilogy with The Liberation of Celia Kahn ten years ago. We’ve twice shared a publisher, yet never met. He was kind enough to send me the limited edition of his sixth novel The Responsibility of Love, which gets a mainstream publication in September. Simons started his career with three decidedly serious novels, the trilogy, and continued with my favourite, about an ageing writing revisiting Japan, An Exquisite Sense of What is Beautiful. The latest, like its predecessor, A Woman of Integrity, about a silent film star turned photographer, is more of a romp. It’s set on the eve of a book prize, where a novelist whose career might finally be vindicated finds his life simultaneously falling apart. There are obvious comparisons with Martin Amis’s The Information and Edward St Aubyn’s Lost for Words, but this is much better than the second and more entertaining than either, not least because Simons’ female characters are interesting and convincing, often possessing more agency than his beleagured men.

Time to return my books to Bromley House, then collect the copy of Luke Kennard’s new novel The Answer to Everything waiting for me at Five Leaves. Happy reading.