The Wirral Line: 1973

I wrote the following for my MA students’ annual anthology, ‘Bystanders’, last year, inspired by its title, but got the ending wrong. I only remembered what I’d forgotten to include, which told me how it needed to end, the one time I read out the piece, at the anthology launch. Good example of why I always tell students the best way to work out what’s wrong with a piece is to read it aloud.

THE WIRRAL LINE: 1973

Aged fifteen, I spend a lot of my Saturdays in Liverpool, mostly in record shops. Usually Probe, on Clarence Street. I sometimes stop by the store that used to be Brian Epstein’s NEMS, on Great Charlotte Street. Often Hairy Records on Bold Street. Always Virgin Records, also on Bold Street: a big, friendly space that smells of joss sticks and has bean bags for customers spread across the floor.

This Saturday I’m wearing a new, blue denim bomber jacket with a patch my mum has sewn onto the left arm. Have a nice day! it reads, accompanied by an image of a cannabis leaf. I know what kind of leaf it was. Don’t think Mum does.

I’m heading home with a white Virgin plastic bag under my arm. The bag has a black and white drawing depicting a pair of conjoined naked girls, each with Pre-Raphaelite hair. The record in the bag is Rockin’ The Filmore by Humble Pie, a double album for the price of a single. ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’ takes up a whole side. The two LPs turn out not to be such a bargain, as there are only two tracks I like a lot, and one of those is a Stones cover. Before the year’s out, I’ll swap it for something better. For a while, though, I’ll be able to convince myself that it’s great.

Leaving Lime Street, the train is busy. I’m going to the end of the line, West Kirby, which is on the tip of the Wirral Peninsula, just below Liverpool. A half hour journey. Most passengers get out at Birkenhead North. That’s where the youths get on. A year or two older than me. One wears braces. All three have drainpipe jeans and metal-capped boots. I’m wearing 28-inch flares, also known as loon pants. My fair hair is not quite shoulder length, but it’s the longest I’m able to get away with at Grammar School, where I’m sometimes referred to as Hippy Dave.

The seats around me have emptied. The three skinheads take them: one next to me, the others opposite. If I’d been thinking quickly, I would have moved. I once saw a bunch of skins give a kicking to a lad I knew on our way to board the Mersey ferry. I know they’re dangerous to be around. Yet I think of trains as safe places. The worst thing that ever happened to me on one was when I lost a new glove.

The skins talk to each other for a minute then take the piss out of my bag. They aren’t interested in the contents, only the design. In 1973, Virgin isn’t yet a name brand. The shops are few and far between, while the record label only launched last year. Does the bag mean I’m a virgin, the skins want to know.

I ignore them. At fifteen, I’m a wimpy, bespectacled teenager, tall but slight, with a chronic daydreaming habit. I’m used to being bullied by my peers. I’ve learnt to deal with the situation by using wit or running away. Neither is an option here.

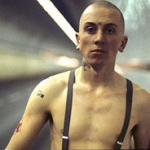

One youth is the ringleader. He does most of the talking, showing off to his pals. Forty-odd years later, he’s the only one I remember. I can’t help but picture him as a leaner version of Tim Roth in Alan Clarke’s Made In Britain, though that was on TV a few years later. He’s nasty, yes, but not without a sense of humour.

Have I ever been to Leasowe Dock, Tim Roth asks. I know nothing about Leasowe, except that it’s one of the stops on the Wirral line. Presumably it’s a coastal town. Like West Kirby, then, but nearer Birkenhead, so probably more industrial. Have I ever been to Leasowe Dock, he repeats. I shake my head. Tim Roth gets out a big metal comb and starts to wave it near my face. I flinch, then lean back, try to avoid being cut. His mates start to kick me with their metal-tipped boots.

Tim Roth doesn’t join in the kicking. He asks me about my patch. Did I sew it on myself? He begins to unpick the stitching with the sharp teeth of his comb. The train stops and starts. The kicking becomes more urgent. The skins raise the volume of their taunts. All three join in. Why don’t we show you Leasowe Dock? Want to take a walk with us down Leasowe Dock? I know better than to reply. The youths’ laughter fills the carriage. Later, I will find that my face is wet.

The Have A Nice Day patch is only a thread or two from coming off when the train stops again. Suddenly, the youths get up. They run out, still laughing. I look outside. This station is Leasowe. They were only traveling two stops.

That night, I’m babysitting for friends of my parents when the doorbell rings. After seeing the state of me, my dad called the Transport Police. Three hours later, they turned up at our house and were directed here, one street away. A pair of thirty-something guys in plain clothes tell me there are no docks at Leasowe. When I’ve failed to give them anything that might identify my attackers, they ask if there were other passengers in the carriage. I tell them that there were. Five or six, at least.

I recall the passengers’ faces. After the skins had gone, each of them avoided looking at me. People much like my parents. One or two probably had kids my age. I don’t blame them for not intervening. The boys were scary. Possibly they thought that I was somehow to blame and deserved what was happening to me. Part of me thought so. Only as an adult does it occur to me that one of them could easily have got off, called a guard. Or, at least, comforted me when the boys had gone.

The police aren’t surprised when I tell them what didn’t happen. Their job has taught them all about collective cowardice. Only one thing arouses their curiosity.

‘Are you sure they said Leasowe docks?’ they ask.

‘Definitely. They kept offering to take me to Leasowe docks.’

‘But there are no docks at Leasowe.’