Serendipitous Reading

Serendipity is, I think, one of the keys to a happy reading life. If you only read in a strict order: books by friends, books that you feel you have* to read, books by authors you always read**, there’s no room for happy accidents, or borrowed books that someone shoves in your hand, or, indeed, rereading.

We had a long trip planned, with multiple flights and train journeys. With that in mind, I had both Tim Shipman’s big Brexit Book*, Country Overboard (or whatever it’s called – too depressing, anyway) and Paul Auster’s** off-puttingly long and trite-sounding 4-3-2-1 on Kindle. Neither got started. On the other hand, the day before we left for Japan, I found two disposable looking third hand books in the charity bin at Wilko. Each looked ideal for reading on the plane and leaving behind. Both were by authors I used to enjoy but haven’t read in well over a decade: Reginald Hill and Ross Macdonald.

Hill’s An April Shroud is an early, and rather silly Dalziel and Pascoe novel, with a slow start that builds into an intricately plotted panto type plot: ideal for plane then hotel reading as I slowly shook off jetlag in Higashi-Hiroshima (home of the world’s best sake, and the university that, so kindly, invited us to work for a week). Before the jetlag set in I also read George Saunders’ Booker winning Lincoln in the Bardo* over two sittings. I’ve read a lot of Saunders, with occasional enjoyment, some admiration but no great love or desire to emulate his bloodlessly show-offy work. I felt the same about this undoubtedly clever story. I’m interested in ghosts. I’d been invited to Hiroshima to talk about my ghost stories, so the genre was on my mind. I don’t think Saunders added a great deal to it. It was occasionally moving, but, overall, the set up felt more Hellazapoppin in the Bardo than MR James. That this OK story won the Booker prize while Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad* didn’t make the shortlist tells you a lot about English literary culture, which admires cleverness more than storytelling. And while we were away the Arts Council announced that sales of literary fiction are in crisis.

We’d taken The Underground Railroad because we both wanted to read it, and weren’t disappointed. Gripping, sharply written, occasionally confusing (we couldn’t entirely agree on whether he tried to cram in too much, nor whether some timelines were deliberately confusing or cleverly patterned). I knew nothing about the underground railroad until a visit to Boston early this century, but this books tells you a great deal about its place in the history of slavery. Occasionally it’s fantastical, at other times gruelling, but the novel’s never boring, and we become deeply engaged with the characters. Superbly structured, it’s mythic, in an uplifting way that – as Saunders proves – is very hard to achieve. Anyway, I don’t want to use Whitehead’s novel (it won the Pulitzer Prize, the one that William Gass said ‘takes dead aim at mediocrity and never misses’) to berate the Booker winner, which I did like, more to draw the novel to your attention, as it’s a cracking, important read.

As was my other Wilco find, Ross Macdonald’s terribly titled The Instant Enemy. I read a load of Macdonald – Chandler’s most direct successor – thirty-odd years ago when John Harvey introduced me to him. Fantastic hard boiled style and intricate plots, often rooted in family secrets, that wind up making much more sense that Chandler’s. That said, I can only have read half the Lew Archer novels, recently collected by the Library of America, and I need to rectify that. This one, from 1968, is notable for its (convincing) use of the then new psychedelic drug, LSD. If you can find a copy, read it.

My other plane read was meant to be the most recent Sue Grafton, but – my Kindle having died, I’ve adopted Sue’s,which she doesn’t use – I happened upon a novel that she’d read a year or two ago, William Boyd’s Sweet Caress, the fictional autobiography of a female photographer who happens to have been around at some of the most interesting points of recent history eg The Vietnam War. It’s not one of the most serious of Boyd’s novels. In some ways it reminded me of J David Simon’s fine 2017 jeu d’esprit A Woman of Integrity** (which I wrote about here). You can tell that the author had fun writing it. Perfect plane read, taking up the first six hours of a nine and a half hour flight from Tokyo to Helsinki.

Last night, I learned that Sue Grafton has died of cancer, aged 77. I didn’t know her, only saw her speak once, alongside John Harvey, who lent me A for Alibi in the mid-80s (John introduced me to a lot of crime writers). I’ve worked my way through the whole alphabet with her. A fine crime writer who never allowed TV or movies to sully the reader’s impression of her convincing, early feminist, intelligent, always entertaining private eye, Kinsey Millhone. Deservedly one of the first winners of the Ross Macdonald literary award, for stories set in California. Her fictional Santa Teresa isn’t a million miles from Macdonald’s fictionalised version of Santa Barbara. I’ll be saving the new Y is for Yesterday to savour at a later date, for her final book, always intended to be called Z is for Zero will now never be written, except in her readers’ heads. RIP.

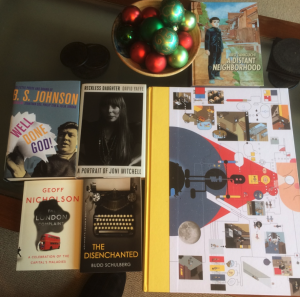

I got a nice pile of books, pictured above, for Christmas, and these will doubtless form some of my reading for the next few months. Though, let’s be honest, Sue just made me move an eighteen inch pile that included several of last Christmas’s books up to my office. The book I’m about to finish is one that James from across the road lent me on our return from Japan: Jiro Taniguchi’s classic graphic novel A Distant Neighbourhood (pictured above, with Geoff Nicholson, Budd Shulberg et al – the really big book is Chris Ware’s Monograph). Pretty sure I’ve read it before, last century, but it stands up brilliantly and means more when you’ve just traveled extensively in Japan (after working in Hiroshima, we also visited Kobe, Kyoto, Kanazawa and the less alliterative Narita, observing vast amounts of the country from Shinkansen bullet trains). A 48 year old man suddenly find himself back in his fourteen-year-old self, just before his father disappeared. It’s a gripping, beautifully illustrated tale about coming to terms with memories and, fittingly, I can’t remember how it ends. But I’m about to go downstairs and find out.

All the very best for the new year to each of you readers.