Brian Moore’s Century

Today is the centenary of the Belfast born novelist Brian Moore, who I’ve been reading for 44 years, since a friend introduced me to his work during the first term of my English and American literature degree. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on Moore’s fiction, supervised by Northern Irish poet Tom Paulin, who was also a Moore fan. He remains my favourite post-war novelist in the English language. Yet when I mention him to people born after 1970, they’ve never heard of him. One has to ask why – apart from his having a rather common name which, nevertheless, nobody knows how to pronounce (it’s Bree-an) – this might be?

I attended an online Moore symposium at the University of Exeter earlier this year and there has been a week-long festival over the last week in Moore’s hometown, Belfast, with a talk by Moore biographer Patricia Craig, several films and panels where novelists Colm Toibin and Bernard MacLaverty are among the speakers. This link and the Twitter hashtag @brianmoore100 are well worth a look, as is this piece in today’s Irish News, which describes Moore as ‘Northern Ireland’s greatest novelist’. Update: the Belfast book critic John Self also wrote this excellent overview for The Critic.

Moore died 22 years ago, aged 77, and writers tend to disappear for a decade or so after their deaths. The majority don’t return, for there are always new novelists emerging, and new readers tend to seek out newer writers. Moore is also a tricky writer to sum up, or sell. He has a deceptively plain style, which can be lyrical and powerfully evocative but is easy to overlook. He wrote a number of pseudonymous thrillers before his career got going (and, later, a screenplay for Hitchcock). His mastery of suspense, seen most in his mature novels, can overshadow the more cerebral aspects of his writing. He makes it look easy.

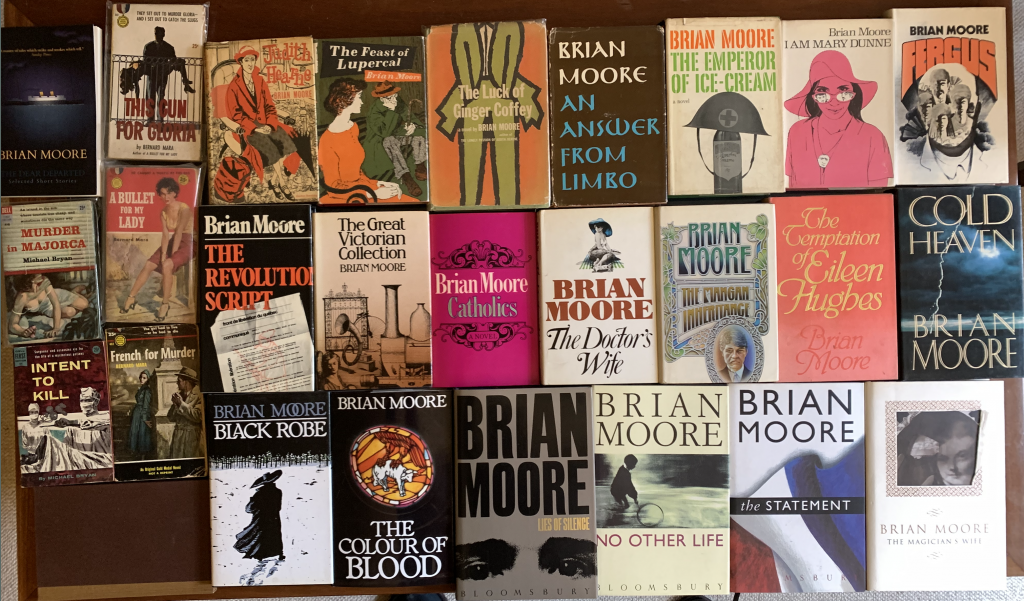

When people ask me where to start, it’s hard to choose. I often recommend the first one I read, which I still regard as his masterpiece The Doctor’s Wife (shortlisted for The Booker Prize in 1976) though Lies of Silence, The Colour of Blood and The Statement (his most thriller-like novels) may be a better way in. There are a few films based on his novels. The film of Judith Hearne is OK, but you’re better off reading his debut novel, bleak as it is. Black Robe is good. Moore wrote the script for The Luck of Ginger Coffey and, in some ways it improves on his third novel, which is hampered – as Moore later admitted in interviews – by being told through the point of view of a relatively inarticulate character.

I learnt most of what I know about point of view from reading Moore’s novels, and interviews with him, back in 1979 and 1980, when I did my undergraduate dissertation. By making extensive use of the inter-library loans system I managed to track down every significant interview and all but one of his published short stories. These have finally been collected, in a fine edition by Turnpike Books (top left of photo below). None are essential, but nearly all are interesting. Turnpike have also reissued three early novels: the fine Feast of Lupercal; the autobiographical The Emperor of Ice Cream and the less successful The Revolution Script. With the exception of I Am Mary Dunne, Moore always wrote within point of view, in what he called third person subjective and achieved intensely effective characterisation through it. I wonder what he’d make of the dominance of the much simpler and (to him) much more limiting first-person narration that increasingly dominates modern fiction.

Here’s the other thing about Moore that makes it hard to sell him to modern readers. All of his novels are different. There are certain themes which recur. Moore’s frequent discussion of modern Catholicism is balanced by an interest in how a kind of fiction takes the place of religion in many lives, as evidenced by his use of Wallace Steven in the title of his most autobiographical novel. Coincidentally, I was taking a year-long seminar on WC Williams and Stevens in my final year, so came to know Stevens’ poetry well and can still recite bits of it by heart. For instance

Let be be finale of seem

The only emperor is the emperor of Ice Cream

And, if I recall, the epigraph from my dissertation was from Stevens’ Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction The Moore novels that best represent Stevens’ idea (put simply, that fiction is a superior replacement for God, for God was always a fiction) are the phantasmagoric The Great Victorian Collection, the less successful Fergusand the fascinating Cold Heaven (made into a half decent movie by the great Nic Roeg). Miracles are at the centre of each novel.

Moore also wrote interesting historical fiction, including the Booker shortlisted Black Robe. When he died, he was working on a novel about the poet Rimbaud’s days as a gun runner. I have a fellowship at the Harry Ransom archive in Austin, Texas, where most of Moore’s papers are held and, if the pandemic ever allows me to take it up, once I’ve finished getting the Greene papers I need (the fellowship’s for research on my novel about the time Greene spent in Nottingham) I plan to see if they have the unfinished draft of that final novel.

Those republished short stories aside, it’s been a while since I’ve read any Moore, the only novelist whose first editions I have assiduously collected over the years (see photo above). I’m doing the final edit on a novel where the number of points of view keep expanding and keeping track of who knows what when is challenging and requires a period of intense concentration. However, yesterday, to honour his centenary I made time to reread his novella Catholics for the first time in over 40 years.

Catholics is set in an imagined future (theoretically the late 1990s but let’s let that pass) where there’s no Pope (only a Father General) and the Buddhist and Catholic faiths are about to merge. Young American Father Kinsella is sent to the remote (and fictional) Irish island of Muck, where priests from the monastery are still going to the mainland to give masses in Latin. These, long since outlawed , have begun to draw crowds from across the world. They have to be stopped. The scene is set with huge economy and Moore’s characteristic suspense. Weather plays its part. The priest is turned away from a boat to the island, manages to find a helicopter, then finds himself forced to stay overnight. Soon, the lines drawn and a subtle battle between Kinsella and the abbot begins. At the halfway point, where you think you can see how things must go, Moore throws in what may prove a game changer:

He thought of the confessions; no-one had mentioned the confessions. They were the biggest danger.

As with the novels that immediately precede Catholics, miracles and their nature are at the heart of the novel, which also captures the Irish landscape and character with great verve and humour. Point of view is used expertly but not slavishly so that in between the two protagonists Moore slips into mind of the monk called Patrick, who is the chief rebel, so that we fully understand him. As with the novels that precede it, faith is the central question.

My grandmother was an Irish Catholic and I was brought up in the Catholic faith, which gives me an additional interest, but you don’t have to share that background to find this story gripping. Like Graham Greene, Moore is able to make spiritual matters feel like life or death to any reader, regardless of their background. There was, by the way, a good TV film of Catholics in 1973, directed by Jack Gold, starring Trevor Howard and a young Martin Sheen. Unfortunately, the only version on the internet is the US Masterpiece Theatre version that trims 15 minutes from the first half hour, significantly diminishing the religious aspect of the story. Even so, I might watch it again, for Moore wrote the script.

One other thing about Moore. He would never take an advance on his novels, which generally took about eighteen months to write. This removed time pressure (albeit relying on his previous sales to support him) and meant that he could abandon a book if it wasn’t working. The only other successful author I know who worked this way was Stanley Middleton (who withdrew Poetry and Old Age when he could not fix it to his liking). But Stanley always had an income from teaching, so Moore’s approach was all the braver.

In writing this brief blog, I checked the Wikipedia entry for Moore, which is pretty good. I found a couple of omissions, sure, but also a link to this final piece, commissioned by Granta just before his death. Movingly, Moore talks about where he wants to be buried, but it’s also his final reflection on the experiences that made him the kind of writer he was.

Belfast and my childhood have made me suspicious of faiths, allegiances, certainties.

Almost any novel of Brian Moore’s is worth reading (even the pseudonymous pulp novels, all but one of which I’ve tracked down, have their pleasures and I’ve included them in my display of first editions). My one regret with Moore is that I never wrote to him to tell him how much his work had meant to me and influenced my own writing. I used to be shy of writing to authors I didn’t know, and I think I wanted to be able to send him a novel I was sufficiently proud of. But by the time I’d written a novel that I considered just about good enough for me not to be embarrassed to share it with a master, he was dead.

Finally, may I recommend his late, great novel No Other Life, about Haiti. A better book than The Comedians (as I suspect even that novel’s author, Graham Greene, would have agreed – Moore was Greene’s favourite living author. This novel came out after his death), it’s Moore’s final masterpiece (although The Statement is very good and I need to reread his final novel The Magician’s Wife) and his most political novel. Anywhere you start with Brian Moore you’ll find something of interest. Most writers end up being remembered for a handful of novels at most. With Moore, there are at least a dozen that deserve serious discussion and repeated reading. He’s a superb stylist with a strong sense of humour, a mastery of storytelling and an acute observer of human behaviour. He will last.