Young Laureate: an essay on Simon Armitage

With this weekend’s announcement of Simon Armitage’s appointment as poet laureate, many of us have been reminiscing about when we first came across him in the late 80’s. My partner, Sue Dymoke, did her first public reading with him in 1987 and our friend John Harvey published him early on in the fine Nottingham-based poetry magazine Slow Dancer (celebrating its fortieth anniversary this year – Sue was the UK poetry editor for many years). 29 years ago, enthused by Simon’s early work, I wrote an essay about him for Slow Dancer. I wanted to give him a boost, but his career was moving so quickly, he’d already taken flight.

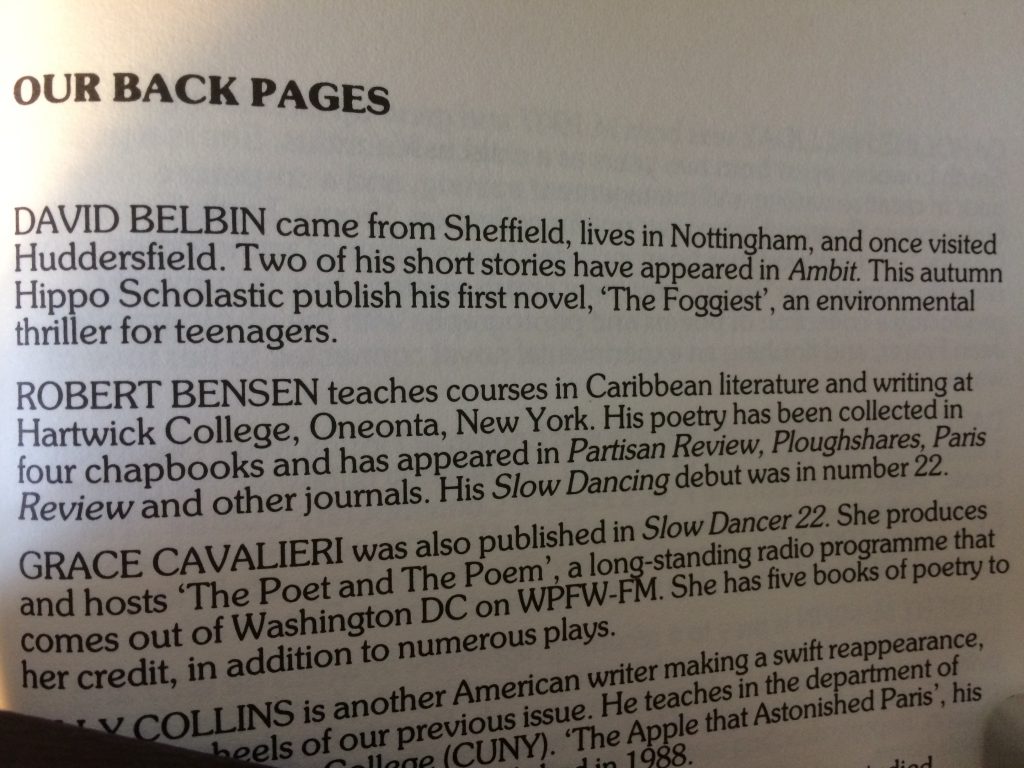

Over on Facebook, Andrew Moorhouse asked me to dig out this first ever essay on Armitage and copy it for him. While I was it, I decided that I might as well OCR the text and put it online. I haven’t changed a word. The cover for the issue is above – a field mouse has chewed away the top corner (it was in our allotment garage and the mice like the taste of small press glue). Here’s my biog note from the back of the issue, which also featured an up and coming name, Billy Collins, and the late, great Tina Fulker.

And here’s the essay. Congratulations, Simon. I’m sure you’ll do a good job.

THE POETRY OF SIMON ARMITAGE

And to think that we once wrote poetry

about the distance between stars, and how

for small things the skin on a surface

of water is almost impregnable.

‘A Place to Love.’

The second half of the eighties has seen a new generation of small press magazines invent itself: The Wide Skirt, The Echo Room , The North and (the late) Harry’s Hand, presenting a distinctly new group of poets. They’re 25-35, mostly male, and mostly live within ten miles of Huddersfield. They go to Peter Sansom’s poetry workshops and none vote Tory, or get published in magazines run by the London Litcrit mafia. Instead, they’ve set up their own alternative version (with, of course, the generous assistance of Yorkshire Arts).

Despite a lot of hard work and rather more poetic talent than Faber and Faber have dug out in the last decade or two, none of the Huddersfield Mafia have managed to make any kind of national impact. Until now. Simon Armitage, at 26, the youngest of these new Northern poets, has just published his first collection (Zoom! Bloodaxe. £4.95). Despite not being feted in any of the publications that Blake Morrison’s friends get reviewed in, Zoom! was the PBS Autumn choice and even got shortlisted for the Whitbread. This kind of success is not so much rare as unheard of. Simon also won a major Gregory award in 1988, appeared last year on radios 3 and 4. If he keeps going at this rate, he should get a South Bank Show special while the 90s are still young.

What makes Simon’s evident success surprising isn’t his age or origins (born in Huddersfield, returned there after university), but that his style is so uncompromisingly original (unlike, say, Wendy Cope, the best-selling new poet of the 80’s). Which doesn’t mean inaccessible:

I can half hear you, John, half see you fumble

with a car battery, a two two air rifle

two wires and a headlamp. You and that shivering dog

going as two silhouettes above Warrington.

His style is conversational. Cars appear in a lot of the poems. There’s always a sense of humour somewhere near the surface, but it’s hard to pin down: equal measures of irony and compassion are directed at his quirky subjects.

None of the poetry in ‘Zoom!’ could have been written by anyone else. What makes the voice so distinct is best summed up in his own words:

It’s often a narrative or yarn, a build up of images and links pebbledashed with a mix of idiom, slang and cliche… although real life is the main ingredient of these poems, they are seasoned with a generous pinch of verisimilitude.

PBS Bulletin, Autumn 1989

Some influences are apparent: like many of the new Northern poets he’s more in tune with the relaxed rhythms and wide ranging subject matter of post-war U.S. poets than their drier, more formal English counterparts. Frank O’Hara gets a namecheck and William Carlos Williams is hanging around somewhere. [an McMillan’s quirky surrealism might be a more local inspiration. Like MacMillan, Armitage’s poems work as well, or better, when read aloud. They share a love for the memorable punchline: ‘no fish: no birds: no shit.’ (‘The Peruvian Anchovy Industry’.) Or ‘My cock’s a kipper’ (‘Bus Talk’).

Armitage also acknowledges influences from rock: it’s easy to identify the tone of David Byrne’s (Talking Heads) deadpan lyrics about Urban American life in aspects of Simon’s style. Don’t Sing’ uses the title of Paddy McAloon’s meditation on Graham Greene (recorded by Prefab Sprout) to tell an absurd yet poignant war story.

Smith Doorstop published ‘Human Geography’ in 1986. It includes ‘Lamping’, quoted above, amongst other equally distinctive poems and several with a rawer approach. By the time it was reprinted two years later, the false starts had been cut — only seven of the original seventeen remain. Some of the cut poems are good, but one gets the sense that Armitage is prolific and has plenty to choose from. Youth isn’t far behind in these poems. ‘Dykes’, despite its predictable puns, somehow links dams with maybe lesbians in wry, revealing couplets:

Later I discovered

She was only pointing to an overflow culvert.

Although we were close, she knew a closer, deeper circle

Which, at seventeen, I found undetectable

And many of her stories held no water

Especially those involving Susan, Gill or Sandra

‘The Distance Between Stars’, which Wide Skirt published the following year, is the best of Simon’s three pamphlets. His style has fully arrived. Bookended with poems on astronomical themes, ‘The Distance…’ moves from the mysterious to the mundane, leaving you never quite sure which is which. Many poems take the form of monologues. These are closer to Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads than to Carol Ann Duffy’s Thrown Voices and range from the bleak, bitter Antarctic narrative “Bylot Island’ to the jokey, condescending mechanic in ‘Very Simply Topping Up the Brake Fluid’. The latter poem manages to convey the broken rhythms of a continuously interrupted monologue, while reading with verve and a rhythmic swing which may be as difficult to write as It is easy to read:

…gently does it, that’s it. Try not to spill it, it’s

corrosive: rusts, you know, and fill it till it’s

level with the notch on the clutch reservoir.

Lovely.

Yet the fact that these poems are accessible doesn’t mean that they’re light. Armitage carries emotion confidently, unafraid to confront sentiment. ‘Gone’ reminds me of Larkin’s ‘Home is so sad’,

Not the bed, empty, that’s

one thing. But her watch, still ticking

and the loop of one, blonde hair

caught in her hairbrush. Ihat’s another.

This ability to let a detail stand starkly in representation of death; the stern laconic phrase which conveys intense emotion: these are the work of a mature, and possibly major poet.

Armitage’s last pamphlet was ‘The Walking Horses (Slow Dancer 1988) which is a consistent, but more varied set than ‘..Stars’. Its major poems are his longest monologue so far, “All Beer and Skittles’ , a cynically comic account of the sacking of a sometime plumber, and ‘Screenplay’, a more speculative, tender, visual poem that could not have been written by many of his peers.

That said, there are qualities that he shares with other new Northern poets: humour, arrogance, awkward sensitivity laced with a generous measure of self doubt, also, a sometimes fussy referential habit (whether to places or people} – Armitage takes all these, but transcends them, making something more original. This was overwhelming apparent later in 1988, when a revised, extended edition of his first book introduced many of the remaining poems to be found in ‘Zoom!’

The bears in Yosemite Park

are swaggering home, legged up with fishing line

and polythene and above the grind of his skidoo

a ranger curses the politics of skinny dipping.

This is life.

Armitage avoids fixed rhythms, attaining a conversational shamble of deceptive pace: walking a kind of metrical highwire. His poems can be read many times and retain their freshness. I recall the excitement of reading ‘Zoom’ for the first time, in issue four of ‘The North’: (The exclamation mark, incidentally, was added later, evidently at Bloodaxe’s insistence) the boldness of the metaphor could have been overbearingly arrogant in almost anyone else’s hands, yet it works as a magical, comic, surreal, and finally quite humble account of the creative process.

The book ‘Zoom!’ (Bloodaxe, 4.95) is a fat first volume which is worth buying even if you’ve got all the pamphlets discussed above, and indispensable if you haven’t. Many of the newest poems seem grittier, more compassionate than his earlier work. His probation worker job may partly account for this, emerging as subject matter in poems like ‘Social Inquiry Report’, ‘Eighties, Nineties’ and ‘The Stuff’. But then some of the final poems in the collection are even harder to classify than any of those I’ve tried to discuss earlier: more wilfully obscure and cynical, yet wistful in tone. And among them, reminding us of his background in Oceanography, is one of the most striking poems about ecology that I’ve read, ‘Remembering the East Coast’.

At conference

how they roared at the chairman’s address,

his much told fable

of the bald patents clerk

who resigned his post circa 1850

explaining ‘Everything we need

is now invented.’

But alone I am with him; dipping the quill,

crossing the t of his signature,

blotting the I’s

of his oddball opinion.

‘Zoom!’ is only a beginning, but a dazzling one, from a poet who’s already past words like ‘promise’ and ‘potential . Finally, it leaves you with the same impulses as all good art: it leaves you wanting more and it keeps you guessing. Give Simon Armitage a test drive.

From Slow Dancer issue 23, 1990. Copyright David Belbin.